By the time I went to Cambridge to study philosophy, I had been devoted to literature for years, and even intended to be a writer, having been producing poetry since I was 13. It was in literature, of all the creative arts, that I sought to learn about human nature and existence. I had thought that the study of philosophy would amount to considering such matters at an even higher level than poetry, but I had the misfortune to be at university in a period when British philosophy was dominated by logical positivism, which rejected all metaphysical notions as well as existentialism ("continental claptrap", opined my director of studies.)

Disillusioned with the courses and lecturers, I found myself devoting much more time and attention to drama, which at least seemed to be concerned with The Meaning Of Life. But I soon came to find the theatre world at Cambridge to be much more petty and cliquey than suited me. I had previously in London been involved with the Hampstead bohemian set, and came to know similar people in Cambridge, some of whom lived in a house in Clarendon St. owned by a recent graduate, Bill Barlow.

It was in a conversation with Bill that he made what seemed to me the radical assertion that my goal of being a creative person was not necessarily the most admirable path. Rather, he insisted, the elevation of consciousness was the greater priority. After all, the quality of one's creative work is bound to be a direct result of one's consciousness, and the most important criterion of its value was surely its effect on the consciousness of others as well.

Nigel Lesmoir-Gordon at that time was living at Clarendon St., and I soon realised that he was already of that persuasion, and it was from him that I learned about such authors as Ouspensky, whose Meetings With Remarkable Men and Tertium Organum were fundamental texts for the expanded consciousness movement, as well as Gurdjieff and R.D. Laing, who was making waves with his novel ideas about altered mental states. Nigel was quite familiar with the beatniks, and introduced me to many of their writings. I soon was spending more time at Clarendon St. than with my fellow students, delighting in conversation with Nigel and his lovely girlfriend,later wife, Jenny.

At about the same time that I left the university in 1965, Nigel and Jenny moved to an apartment in London, also owned by Bill Barlow, at 101 Cromwell Road. Once again I was drawn to their company time and again, and after living for a few months in Marylebone, I moved in to the room next door to theirs. Thus began the most intensely transformative period of my life to date. It's hard to believe that it really only spanned about three years, so full of experience and realisations was it. The history of 101 is well-known; the myriad of underground writers, artists, musicians and psychonauts who frequented the place has become legendary. Nigel was the most congenial of hosts, and Jenny brought a cleverly mischievous charm to all occasions, and there was hardly an evening when there were not several or many visitors, quite often enjoying the LSD that arrived there via Michael Hollingshead and John Esam before it was known at all in London.

Many histories of the 60s present the 101 scene as if it revolved around Syd Barrett of the Pink Floyd, who lived there at various periods, and perpetuate the perspective typical of journalists and fans, namely that the most famous person in a group is the centre of it, implying that the people sharing space with him at 101 Cromwell Road and later at Egerton Court were "camp-followers" or "hangers-on." Nothing could be farther from the truth. Just about everybody there had his own thing; most were there before he came, and some of them were his childhood friends. The creative atmosphere owed less to him than to such residents as Nigel, poet John Esam (who co-organised the Albert Hall Poetry Festival), photographer Dave Larcher, graphic artists Storm Thorgerson and and the others who formed Hipgnosis, visual artist

David Gale (Lumiere & Son), poet-author of The Book of Grass George Andrews, budding alchemist

Stash Klossowski de Rola, etc., etc. Other visitors to 101 included Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, Kenneth Anger, Donovan, Marianne Faithfull, Alex Trocchi, and various Stones and Beatles. A much longer list could be made, but the point is that Syd was there because it was a matrix from which sprang the 60s London psychedelia. Of course, in addition to the psychonauts there were people who came merely because it was a Scene, people stuck at the level of personalities. Interestingly enough, many of these are the ones most eager to be interviewed about the carryings-on there, and their accounts often miss the essence as much as they themselves missed the point then through their exclusive focus on personalities.

At that time I was working as assistant to Robert Fraser (Groovy Bob) at his gallery in Duke St., which became one of the principal nodes of Swinging London. Through Fraser I met and became good friends with

Christopher Gibbs, the two of them being central figures in a bohemian aristocrat set to which several Rolling Stones and Beatles were also attracted. I introduced Nigel to these people, and he and Jenny were immediately accepted with great enthusiasm. After all, few couples merited the term "The Beautiful People" as much as they did, and many of these privileged people and celebrities were becoming turned on to acid and welcomed the transcendental perspective that we sought to share, which interpreted the psychedelic experience as cognate to the experiences of mystics and occultists.

At that time there were basically two schools of thought about how LSD was best taken, which one might call the Leary school and the Kesey school. The latter, with its extroverted antics and missionary zeal, is well described in Tom Wolfe's Electric Koolaid Acid Test. The Leary/Alpert approach was based on eastern spirituality, though no less proselytising. Nigel, like most of us, was of that leaning, and our explorations of Buddhism, Taoism, Jung's writings and many other esoteric works gradually led many of us to a search for the ideal method of attaining what we were still bold enough to call Enlightenment.

It was in the company of Nigel and Jenny that my transition to vegetarianism began. While full-on tripping,we went to a restaurant and ordered a meal. When it came, I stared at my veal escalope in horror, muttering "Baby calf flesh", while Jenny gazed in dismay at her omelette. "Baby chickens,", I believe she whimpered. I can't remember what Nigel had ordered, but that experience pretty much converted me to a vegetarian diet. It was at another restaurant meal, incidentally, that I placed in a moment of verbal ineptitude an order for "a glass of two milks", a phrase that will live in infamy, now that Nigel has used it as the title of one of his recent novels.

It was from Nigel that I first learned about a Master in India who seemed to have all the qualities of a true master, as distinct from the many questionable gurus who appear in profusion, levitating, collecting Rolls Royces and materialising watches, etc. Several friends had been to his ashram, or Dera as it was called, and came back with glowing testimony to his being The Real Thing. It was not long, therefore, before Nigel and Jenny, myself and Adrian Haggard obtained permission to attend the Radha Soami Satsang in Beas, Punjab. Adrian and I set out to hitchhike to the Punjab, which was an adventure in itself, and we met up with Nigel and Jenny there. Over the next few weeks we experienced the amazing aura and wisdom of the master, Charan Singh, and as our stay there ended, we all received initiation into the practice of Shabad Yoga, the yoga of internal sound. Without doubt this has proven the most significant turning point in all our lives.

Nigel and

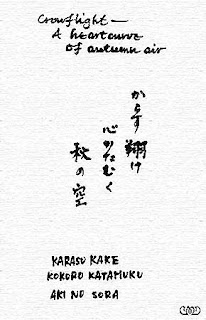

Jenny returned to England, and I headed east, hitchhiking and working my way on ships until I reached Japan, where I have been pretty much ever since. We've got together several times over the years, in England and in India, and they remain among the most loved people in my life, true spiritual colleagues. Many of my best memories are of things said or written or otherwise learned from or together with them. If any one thing epitomises the shared vision we had from the start of what we might become, it is probably a Chinese poem Nigel had written out and pinned to his wall, which seemed to sum up the ultimate goal as not at all the gravitas of Enlightenment, but the shared delight of heightened awareness.

"When two masters meet

They laugh and laugh--

The trees, the many fallen leaves."